Cloud Republic

This week: A/I and the new civic frontier.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

― Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future

In 1956, the Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley of Bell Labs. The three physicists had invented the transistor, the foundation of what quickly became known as the Information Age, a few years earlier, in 1947.

Everything which drives our modern global society — all of it, from the cellphone in your pocket to the most powerful supercomputer — can be traced to their work benches.

It’s astounding, when you think about it: one piece of technology revolutionizing the world. Strictly from the perspective of scale, the potential of one new gizmo, especially one as tiny as a transistor (think computer chips), to upend everything before it seems, well, unlikely. Big things should be caused by big things, we think.

But that wasn’t the case. The invention of the transistor upended and transformed the world’s economy while revolutionizing the way we live. Everything which came after it was different from everything which came before.

And it wasn’t the first time.

A Movable Feast

Almost exactly 500 years before the Bell Labs team experienced their voilà moment, a German craftsman and inventor named Johannes Gutenberg designed and built the first metal movable-type printing press. Like the team at Bell Labs and so many other inventors through the ages (hello, Thomas Edison), Gutenberg didn’t set out to change the world. He was trying to make a buck.

But change the world he did, and in some unexpected ways. He probably never considered how the relatively easy and affordable dissemination of knowledge and ideas would affect European society, and ultimately the course of history, but everything was different after the invention of the printing press.

One of the biggest changes involved who exactly could even read. Outside of the clergy and the extended royal houses, most people in the Middle Ages were illiterate. Now, with books becoming more and more widely available, the ability to read became more and more commonplace.

A socio-cultural revolution was on. And as is always the case in human affairs, before too long it became political. Per Wikipedia:

The printing revolution occurred when the spread of the printing press facilitated the wide circulation of information and ideas, acting as an "agent of change" through the societies that it reached. Demand for bibles and other religious literature was one of the main drivers of the very rapid initial expansion of printing. Much later, printed literature played a major role in rallying support, and opposition, during the lead-up to the English Civil War, and later still the American and French Revolutions through newspapers, pamphlets and bulletins.

In a way, what we do at the Institute harkens back to the time of pamphleteering. The tools may be dramatically different, but the idea is the same: put your ideas in understandable form and use the tools at hand to disseminate them as widely as possible.

Whether the capability of doing that through the internet is, in general, a good or bad idea is a subject for another time. The important thing for us today is to understand how great a role technology has always played in the story of human civilization.

The invention of the wheel was technology. The discovery of fire was technology. So were the first cave paintings, the first attempts at written language, the invention of the abacus, and the advent of weaponry.

That last one perhaps is the most uncomfortable to acknowledge, but also the one least possible to ignore. It’s a sad but unavoidable fact: military conflict has been the driving force behind far too much of our technological progress. The need to find ever more efficient ways of harming each other, and ever more efficient ways of defending ourselves from harm, has been the source of our most dramatic leaps forward.

Necessity, you see, truly is the mother of invention.

Fortunately, as time has gone on, we truly have become more civilized, at least on a global basis, and in general:

📉 The Decline of Violent Conflict Over Time

- Fewer deaths per capita: While the 20th century saw devastating global wars, the rate of conflict-related deaths per 100,000 people has declined dramatically since World War II. This trend holds even when accounting for population growth.

- Holtzman’s Law of War: The data shows that although conflicts still occur, they are generally less deadly than in the past. The two World Wars were outliers in terms of scale and lethality.

- Post-WWII peace dividend: The post-1945 international order, with institutions like the UN and a rise in democratic governance, has coincided with a marked reduction in interstate wars and mass-scale fatalities.

- Recent upticks, but not reversals: While the 2020s have seen increases in conflict deaths — notably in Ukraine, Ethiopia, and Gaza — the overall trend remains far below 20th-century peaks.

- Conflict is increasingly localized: Modern conflicts tend to be civil wars or insurgencies rather than global wars. These are tragic and destabilizing but typically result in lower total death tolls than past world wars.

You can explore the full dataset and visualizations on Our World in Data’s “War and Peace” page. It’s a goldmine for contextualizing long-term trends.

Sources:

Our World in Data – War and Peace

Global Peace Index 2023 – Vision of Humanity

[Graphic created using Microsoft Copilot.]

Which brings us back to the printing press.

You see, while Gutenberg’s movable-type printing press may have made books and other printed materials accessible to almost everyone, and the accessibility meant more people would learn to read, and through reading encounter a variety of ideas, some often radical, and some people would act on those ideas and spark a violent revolution, or start a war, or propose a new social, political or economic system (or a system which covered all three) which would upend the global, or at least European, order, that wasn’t his intent. In fact, it’s doubtful he even had an inkling of what he had wrought.

And neither, of course, did the printing presses themselves. They’re just machines. It was up to us to understand how to use them, to what purpose, and for what reasons. They could serve good or evil, progress or oppression, in equal measure, depending on who was at the controls, but the machines themselves were neutral.

And as the data show, ultimately we’ve done all right. As much as we’ve used science and technology historically to find new and creative ways of obliterating each other, the general trend has been to do it less and less, even as our material abundance has grown. Just as the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, the arc of our material world bends toward progress.

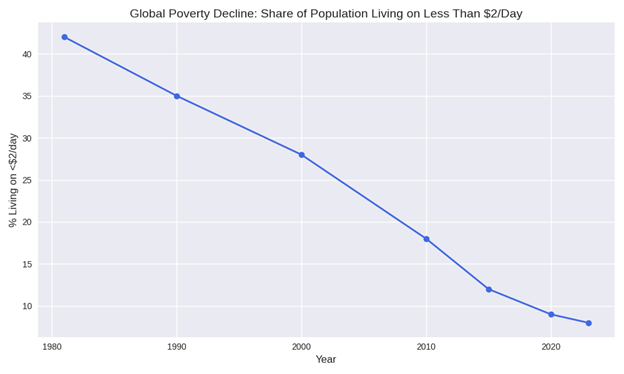

1. In 1981, about 42 percent of the world’s population lived on less than $2/day.

2. By 2023, that number had dropped to just 8 percent, despite global population growth.

3. This progress reflects economic development, international aid, and targeted poverty reduction programs, especially in Asia and parts of Africa.

4. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a temporary spike in poverty rates in 2020, but recovery efforts have helped restore the downward trend

It may not ever be possible to quantify the positive effects of technology on the human condition. And we all know correlation isn’t causation. But to look at it from a broad and objective view, it’s impossible to avoid the conclusion the world has gradually gotten less violent and more prosperous as technology has gotten more robust and more prevalent.

Gutenberg’s revolution may have been inadvertent, but it’s hard to deny the role it’s played in the progress of the last five centuries. Now there is another revolution underway. And it’s not going to take hundreds of years to utterly transform the way we live.

It’s happening already.

Ahead in the Clouds

I’m talking, of course, about artificial intelligence. We have a series on A/I in development for the Modern Whig Leader touching on a variety of issues, not the least of which is the role of public policy in a tech-driven social, business and entertainment environment which is augmented, applied and adaptive. It’s a theme we have a lot to say about.

But it’s important to understand, those aren’t just buzzwords. We’re in a revolution even more profound than the Information Revolution of the 15th Century or the Industrial Revolution of the 18th. As Karl Marx once observed — and in this, for once, he was right — change the means of production and you change the nature of work. Now, the nature of work is changing us.

And as is so often the case, the first place we see the change is in economics. The A/I Revolution (there’s nothing else to call it) needs an enormous amount of capital in order to even occur, let alone thrive. The companies operating in the space are having no trouble finding it, as even a cursory glance at the business pages will show. Stock markets are booming, and the gains are driven almost entirely by A/I.

Whether the buy-side enthusiasm of the stock pickers is driven by simple greed or a vision of what A/I could come to mean for the fate of humanity is an open question (it’s the greed), but it hardly matters. What does matter is the vision.

And the opportunity.

First up is the A/I boom. Project out from the enormous scaling we’re seeing today, and you rapidly run into the pacing challenge: energy. Deloitte estimates power demand from A/I data centers could hit 123 gigawatts (GW) by 2035 in the United States alone. To give you an idea how much energy that is, one gigawatt can power about 830,000 homes. Currently, our domestic A/I data centers are consuming about 4 GW.

That’s not an expansion. That’s an explosion.

But let’s assume we somehow manage to find a way to power the boom. What will we use it for? What’s the purpose of A/I — or as practitioners like to say, the use case? What are the reasons to have it at all?

Techno-advocates often struggle to answer questions like those. It’s tempting to say it’s mostly because they don’t know, and there’s some truth to that. When you’re blazing a new trail and making deal upon deal along the way, usually measured in billions or even tens of billions of dollars, while constantly innovating to stay ahead of the other guys who are doing the same thing, philosophical questions tend to get pushed aside.

But those questions matter. The incredible power of A/I isn’t just measured by the consumption of gigawatts. It’s also measured in the power of the tools it gives large institutions — government, business, finance — and small ones, even individuals, alike. We’re only beginning to scratch the surface; we only have a few of the answers.

One thing we do know: in terms of public policy, A/I will cut both ways, as so many technological breakthroughs do. On the one hand, we’re in a very murky regulatory environment, where questions of free speech and free enterprise run smack dab into issues of privacy, accountability, restraint and control.

On the other hand, we have the ability to design a new way of governing ourselves, a new system of organizing our society (or societies, if we embrace the whole world), something more decentralized, responsive, and aligned with democratic values than the stultified, special interest-oriented way we go about it now. Distributed computing could lead to distributed power — a cloud republic.

Whether we can get there or not depends first on our will to do it, and second, on our wisdom to do it well. In our series on A/I, we’re going to examine all of it. Hopefully, we’ll find the right questions, and then answers we all can live with.

Addendum

Often, technological innovation prompts a backlash as jobs are lost. We’ve all heard of the Luddites smashing machines during the Industrial Revolution, and in modern times, blue collar jobs tend to be the ones eliminated by automation.

But as with so much in our Age of Acceleration, that’s no longer the case. One of the more remarkable aspects of A/I is how flexible it is, and how quickly its capabilities are growing. It’s getting so good, in fact, former consultants are training it to do … consulting.

While Project Argentum is meant to offer consulting firms an opportunity to outsource some of the grunt work typically performed by entry-level staffers to AI, it could also allow some users to bypass management consultants entirely, particularly for those tasks typically performed by junior workers.

In a sign of how AI is already starting to reshape some industries, Amazon.com Inc. recently unveiled plans to eliminate roughly 14,000 corporate jobs. And earlier this week, veteran Wall Street dealmaker Paul Taubman warned that the billions of dollars flowing into the AI sector will bring about changes that threaten to upend the global economic system.

Read the whole thing: Ex-McKinsey Consultants Are Training AI Models to Replace Them - Bloomberg

Immediacy bias makes us think A/I has suddenly come out of the blue, but in fact, it’s been developing for decades. What’s changed the game is the capability of the chips (hence the amazing growth of Nvidia).

But the ideas have been around for a while, and we’ve been groping our way forward in this field for quite some time:

🧠 Timeline of A/I Development

- 1943: McCulloch and Pitts publish a paper on artificial neurons, laying the groundwork for neural networks.

- 1950: Alan Turing proposes the idea of machine intelligence and introduces the Turing Test to assess whether a machine can think like a human.

- 1956: The term “artificial intelligence” is coined at the Dartmouth Conference, led by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, and others. This marks the formal birth of AI as a field.

- 1960s–1970s: Early AI systems focus on symbolic reasoning and problem-solving. Programs like ELIZA simulate human conversation, and SHRDLU manipulates virtual blocks using natural language.

- 1980s: Rise of expert systems — rule-based programs used in medicine, finance, and engineering. These systems mimic human decision-making but struggle with adaptability.

- 1997: IBM’s Deep Blue defeats chess champion Garry Kasparov, showcasing AI’s ability to master complex strategy.

- 2000s: Machine learning gains traction. Algorithms begin learning from data rather than relying solely on rules.

- 2012: Breakthrough in deep learning with AlexNet, a neural network that dramatically improves image recognition. This sparks a wave of innovation in computer vision, speech, and natural language processing.

- 2016: Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo defeats world champion Lee Sedol in Go — a game previously thought too complex for machines.

- 2020s: Emergence of foundation models like GPT, BERT, and DALL·E. These models generate text, images, and code, enabling augmented intelligence across industries.

- 2023–2025: A/I becomes a strategic asset in nonprofit leadership, editorial architecture, and civic technology — including our work at the Modern Whig Institute. The focus shifts from automation to collaboration, insight amplification, and infrastructure design.

Sources:

Coursera – History of AI

Wikipedia – Timeline of Artificial Intelligence

Britannica – History of Artificial Intelligence

[Timeline created by Microsoft Copilot.]

As you may have noticed, sharp-eyed reader, I’ve been using A/I myself throughout this article. Not for the actual writing — it may be a while before I get replaced —but for things like graphics and timelines. I also work with Microsoft Copilot all day in doing administrative tasks, keeping me organized as I balance my Institute workload with the demands of my paid profession and my health adventure.

And I’m not alone. At the Proimpact ED Summit, every single nonprofit executive director talked about their use of A/I and how vital it was to their work. We all operate on shoestring budgets, and often (as with the Institute) on a volunteer basis. Having an assistant like Copilot is worth several paid positions we can’t afford.

That’s part of the promise of A/I. At its most basic level, it leverages technology to turbocharge the productivity of the individual. If it was nothing more than that, it would be a tremendous innovation, one which small businesses and entrepreneurs would quickly learn they couldn’t live without.

But the next step, and one which the field is already taking, is agentic A/I. That’s probably the place where most people, trained in the science fiction tropes of computers run amok, start to get very nervous. And that’s something we’ll address directly, and comprehensively, in our upcoming series.

As always, thank you for reading.

To get the Sunday Wire and the other content of the Leader delivered to your inbox, simply hit the Subscribe button and leave us your name and email address.

To join the Modern Whig Institute and support our mission of civic research and education, click here.

Kevin J. Rogers is the executive director of the Modern Whig Institute. He can be reached at director@modernwhiginstitute.org.

Comments ()